Mass Spectrometry (MS) of Organic Compounds

How Does Mass Spectrometry Work?

- Mass spectrometry operates through three fundamental steps: ionization, separation, and detection.

- Each step plays a critical role in generating a mass spectrum.

- Ionization:

- The sample is bombarded with high-energy electrons, causing the molecule to lose an electron and form a positively charged ion, known as the molecular ion (M⁺).

- This ion may remain intact or fragment into smaller ions.

- Separation:

- The ions are accelerated into a magnetic field, where they are separated based on their mass-to-charge ratio ($m/z$).

- Since most ions have a charge of +1, the $m/z$ value typically corresponds to the ion’s mass.

- Detection:

- A detector measures the abundance of ions at each $m/z$ value, producing a mass spectrum, a graph with $m/z$ values on the x-axis and relative abundance on the y-axis.

The Molecular Ion (M⁺): A Key Starting Point

- The molecular ion (M⁺) is the ionized form of the entire molecule, with no fragmentation.

- Its $m/z$ value corresponds to the molecular weight of the compound.

- Identifying the molecular ion peak is often the first step in analyzing a mass spectrum.

If a compound produces a peak at $m/z = 86$, this peak likely represents the molecular ion, indicating that the molecular weight of the compound is $86 \text{ g mol}^{-1}$.

Fragmentation Patterns: Clues to Structure

- When the molecular ion breaks apart, it forms smaller fragments. Each fragment corresponds to a specific part of the molecule, and its $m/z$ value provides clues about its identity.

- By analyzing these fragmentation patterns, you can deduce structural features of the compound.

Common Fragmentation Patterns

- Certain bonds in organic molecules are more likely to break during ionization, leading to predictable fragmentation patterns.

- Here are some common examples:

- Cleavage of Alkyl Chains:

- Straight-chain alkanes often fragment at C-C bonds, producing alkyl cations.

- For example, propane ($C_3H_8$) may fragment to form $CH_3^+$ ($m/z = 15$) or $C_2H_5^+$ ($m/z = 29$).

- Loss of Small Molecules:

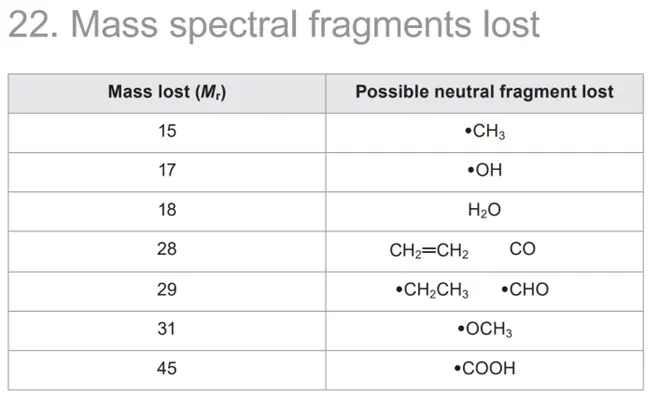

- Mass spectral fragments lost are outlined in Section 22 of the Data Booklet (e.g., $\cdot CH_3$ or $\cdot OH$).

- Cleavage at Functional Groups:

- Ketones and aldehydes often undergo cleavage near the carbonyl group, forming acylium ions ($RCO^+$).

- Molecular ion peak: $m/z = 46$ (corresponding to $C_2H_5OH^+$).

- Fragmentation peaks:

- $m/z = 31$ ($CH_2OH^+$, loss of $CH_3$).

- $m/z = 29$ ($C_2H_5^+$, loss of $OH$).

Interpreting a Mass Spectrum Step-by-Step

Analyzing a mass spectrum involves a systematic approach:

- Identify the Molecular Ion Peak:

- Locate the peak with the highest $m/z$ value.

- This represents the molecular ion (M⁺) and provides the molecular weight of the compound.

- Analyze Fragmentation Peaks:

- Compare the $m/z$ values of the fragments to known patterns (e.g., alkyl cations, loss of small molecules).

- Use the differences between peaks to deduce which bonds are breaking.

- Reconstruct the Structure:

- Combine the information from the molecular ion and fragments to propose a structure for the compound.

- Molecular ion peak: $m/z = 58$ (corresponding to $C_4H_{10}^+$).

- Fragmentation peaks:

$m/z = 43$ ($C_3H_7^+$, loss of $CH_3$). - $m/z = 29$ ($C_2H_5^+$, loss of $C_2H_5$).From these fragments, you can deduce that the compound is a straight-chain alkane with four carbons.

- What does the molecular ion peak represent in a mass spectrum?

- If a compound has a molecular ion peak at $m/z = 72$ and a fragment at $m/z = 57$, what is the likely fragment lost?

- Why might the molecular ion peak be absent in some spectra?